Alcohol and liver disease

Last updated Feb. 20, 2024, by Marisa Wexler, MS

Alcohol is one of the most widely used recreational drugs in Western countries. But according to the World Health Organization (WHO), alcohol consumption can contribute to more than 200 diseases, injuries, and other health conditions.

In particular, alcohol is the leading cause of preventable liver-related conditions and death. In countries such as the U.K., nearly 90% of deaths attributed to alcohol are specifically due to alcoholic liver disease — now referred to as alcohol-related liver disease — the most common form of advanced chronic liver disease in the world.

Drinking alcohol in any amount has the potential to cause health problems, but the risk of liver disease is greatest in people who consume alcohol regularly and/or excessively. As a result, it is important to understand how alcohol affects the liver.

For some individuals, knowledge about what alcohol does to the liver may help them better understand its role as a risk factor in alcoholic fatty liver disease and other related conditions.

Alcohol’s effect on the liver

When ingested, alcohol is absorbed through the gastrointestinal tract directly into the bloodstream, which carries it out to the rest of the body. Because alcohol in the blood is primarily metabolized by the liver, there is a particularly strong connection between alcohol and liver disease. However, excessive alcohol in the blood can also weaken the immune system and cause problems in the brain, heart, lungs, and other organs.

A large number of studies have focused on how alcohol affects the liver. The mechanics are fairly straightforward: Within the liver, alcohol goes through a series of chemical reactions that ultimately convert the drug into other molecules that can be harmlessly processed by the body. However, these chemical reactions generate a series of byproducts and intermediate molecules that are toxic to liver cells.

Thus, while the liver can process small to moderate amounts of alcohol, hepatic injury — or liver damage — can occur when the organ has to clear large amounts of the drug. Continued intake of alcohol in large amounts will then cause further damage the liver, which can become permanent and eventually lead to liver failure.

The risk of developing alcohol-related liver disease, and subsequently liver failure, from alcohol is highest in heavy alcohol users. Importantly, because men tend to be larger on average and have different fat distributions than women, the amount of alcohol considered heavy use varies between sexes.

According to the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, part of the National Institutes of Health, heavy drinking is defined as:

- five or more drinks on any day or 15 or more drinks per week in men

- four or more drinks on any day or eight or more drinks per week in women.

These definitions assume that a standard drink contains about 14 grams of alcohol — roughly the amount in a can of beer, a glass of wine, or a shot of hard liquor.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration also considers heavy alcohol use as binge drinking. Specifically, binge drinking is defined as consuming about four to five drinks within a couple of hours at least five days per month.

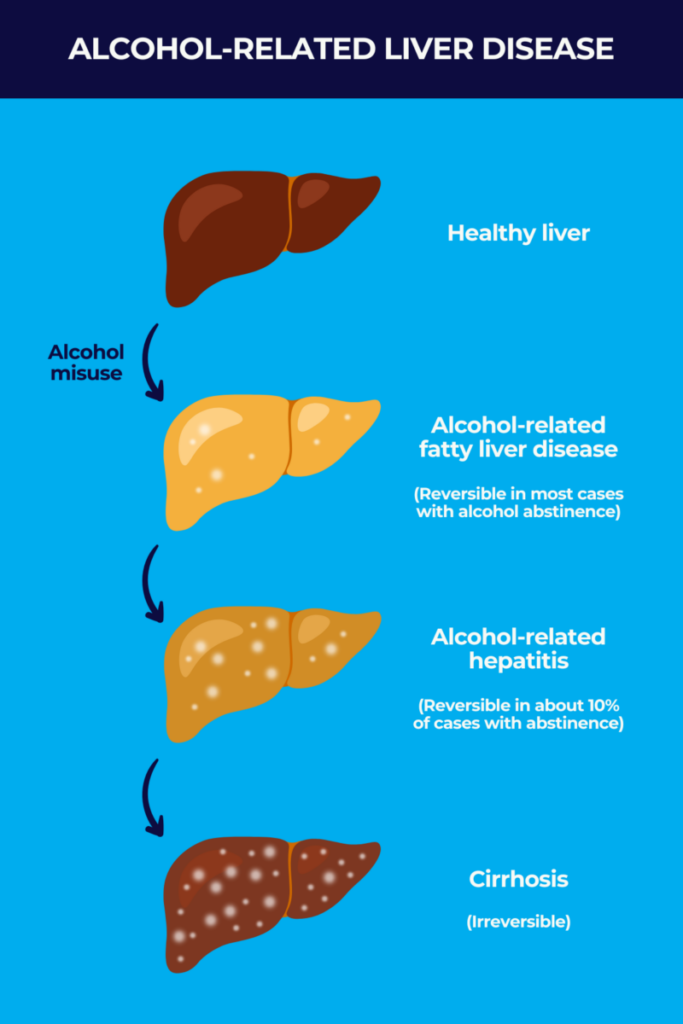

Alcohol’s effects on the liver can cause progressive liver damage that typically occurs in three steps: first, alcoholic fatty liver disease, then alcoholic hepatitis, and cirrhosis.

Alcoholic fatty liver disease

The first stage of alcohol-related liver damage is alcoholic fatty liver disease, which is now known as alcohol-associated liver disease or alcoholic liver disease. One of the effects of alcohol in the liver is a change in the uptake, production, and clearance of fatty molecules in liver cells. This may eventually lead to an abnormal buildup of fat in the liver, known as steatosis.

Fatty liver disease is quite common, especially in heavy drinkers. Most people who consume four to five standard drinks per day over decades will develop steatosis.

In most cases, an alcohol-related fatty liver does not cause any noticeable symptoms, and the first signs of liver damage from alcohol are only detectable via medical examination. About one-third of patients may have an enlarged liver, which may be detected via abdominal scans.

As the liver has a unique capacity to repair itself after damage, this stage of alcohol-related liver disease is generally reversible if the person stops consuming alcohol. However, if left unmanaged, alcohol-related liver disease can progress to alcoholic hepatitis.

Alcoholic hepatitis

In some people with alcohol-related liver disease, sustained alcohol consumption will lead to further liver damage and liver inflammation — a stage known as alcoholic hepatitis or alcohol-related hepatitis. The factors that determine who will experience such disease progression are still not very well understood.

People who engage in heavier alcohol consumption are generally at higher risk, but the association between the quantity of alcohol consumed and the degree of liver damage varies from person to person. Other factors, such as lifestyle and genetics, may play a role in determining who does or doesn’t progress to alcohol-related hepatitis.

Unlike with an alcohol-related fatty liver, a number of signs and symptoms are linked to alcohol-related hepatitis. Patients may experience:

- fatigue or weakness

- fever

- jaundice, or yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes

- abdominal pain, especially in the upper right part

- an enlarged liver and spleen

- nausea and vomiting

- loss of appetite, poor nutrition, and weight loss

- reduced blood flow in the liver

- ascites, or the buildup of fluid in the abdomen

- kidney problems

- confusion or disorientation.

Treatment of alcohol-related hepatitis usually relies on abstaining from alcohol. But because the liver produces a digestive fluid named bile and liver damage may impair digestion, nutritional support also is a standard approach to treatment. It aims to ensure adequate nutrient demands are met and to reduce any digestive problems.

Corticosteroids, a type of anti-inflammatory medication, also can be given to people with severe alcohol-related hepatitis to ease symptoms.

With continued abstinence from alcohol and proper management, alcohol-related hepatitis will reverse in about 10% of patients. Conversely, the disease will progress to cirrhosis in about 10% to 20% of cases on a yearly basis. Mild alcohol-related hepatitis is generally completely reversible with alcohol use cessation, while severe disease will rapidly progress and result in poor outcomes.

A number of factors can be used to inform the prognosis for individual patients in their specific situation. For example, if a person with severe alcohol-related hepatitis doesn’t stop drinking, their five-year survival is estimated to be lower than 30%, compared with a 75% survival rate for those who permanently abstain from alcohol.

Clinicians can calculate risk scores to help determine the best course of action for each patient and may advocate for more pronounced lifestyle changes among those at higher risk of progressing to cirrhosis.

Cirrhosis

Cirrhosis is the final stage of alcohol-related liver disease, where liver tissue becomes extensively and irreversibly scarred, interfering with liver function. Cirrhosis progresses from a compensated phase — in which the undamaged and working parts of the liver compensate for the damaged regions — to a decompensated phase, in which scar tissue is predominant and the liver can no longer function properly.

People with compensated cirrhosis may have mild or no symptoms. But those with more advanced cirrhosis may show symptoms ranging from those of alcohol-related hepatitis and muscle wasting to serious complications such as portal hypertension and liver failure. Portal hypertension, which can itself result in life-threatening events, refers to an increase in blood pressure in the portal vein, which carries blood from the gastrointestinal system to the liver.

Liver cirrhosis from alcohol not only sets the stage for liver failure, but also increases the risk of cancer in the liver. In individuals with cirrhosis and end-stage liver failure from alcohol, the only definitive treatment is a liver transplant, which must be accompanied by continued abstinence from alcohol.

Is there a safe level of drinking?

According to the WHO, no amount of alcohol use has been proven to be safe for people’s health. Based on available data, any amount of alcohol consumption increases the risk of health problems.

That said, some patterns of alcohol consumption are generally riskier than others. The chance of developing alcohol-related liver disease or liver failure from alcohol is much higher for people who drink heavily, compared with those who drink more moderately or infrequently.

As noted above, heavy drinking can be considered as having at least four or five drinks on any day, at least eight to 15 drinks per week, or about four to five drinks within a couple of hours on five or more days per month. Consuming less than this is likely safer for a person’s general and liver health.

Reducing the risk of liver damage

The most effective way to prevent alcohol-related liver damage is to refrain from alcohol entirely. But for people who choose to continue consuming alcohol, the key to reducing risk is moderation. Moderate drinking means no more than one drink per day for women or two per day for men — and avoiding binge drinking.

In addition, other lifestyle choices can be important for maintaining liver health and preventing alcohol-related liver disease. These include things like eating a healthy diet, increasing and/or limiting the consumption of certain foods, and getting regular physical exercise.

People who are at higher risk of a fatty liver or liver disease also are also encouraged to talk with their healthcare team to set up regular liver health checkups so that any issues can be detected and addressed promptly.

Liver Disease News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

- New test detects hepatitis B in 1 hour with a finger prick: Study

- Noninvasive combo tests for liver damage could replace biopsies in PBC

- With Livmarli approval, PFIC patients in Canada have new itch relief option

- Coalition to push for earlier diagnosis of fatty liver disease MASLD

- I’m grateful my son has a care team that truly cares