Brain changes seen in children with neonatal cholestasis: Study

Imaging changes could help detect impairment early

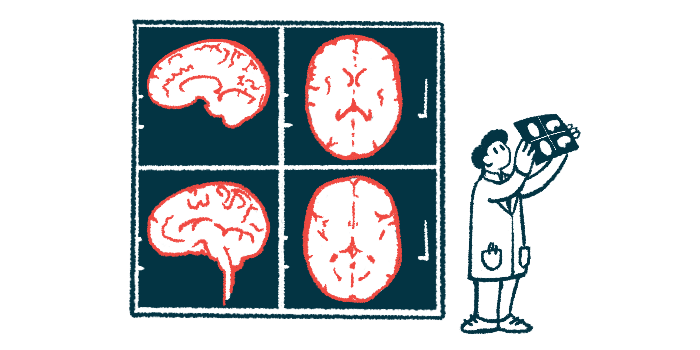

Brain scans have shown children with neonatal cholestasis tend to have brain abnormalities, a review study found. Bleeding was the most common, especially in those with blockages in the bile ducts that carry the digestive fluid bile from the liver to the intestines.

Some brain alterations were resolved after liver transplantation, a therapeutic intervention for severe cases of cholestasis.

The findings suggest that brain abnormalities may partly explain the neuropsychological impairment often observed in children with neonatal cholestasis. Understanding when and how these changes occur may make it possible to intervene early in development.

While the data didn’t establish a cause-and-effect relationship between brain changes and neuropsychological problems, “this review has given rise to some important questions worth further exploration,” the researchers wrote.

The review study, “Brain imaging in children with neonatal cholestatic liver disease: A systematic review,” was published in Acta Paediatrica.

Neonatal cholestasis linked to developmental delays

Neonatal cholestasis occurs in newborns when the flow of bile, a digestive fluid, is slowed or stalled. This leads to bile buildup in the liver, damaging the organ, and bile acid leakage into the bloodstream, causing a wide range of symptoms.

The most common cause of pediatric cholestatic liver disease is biliary atresia, a rare condition affecting infants that is marked by blockage or absence of bile ducts outside the liver.

An earlier systematic review showed “children with cholestatic liver disease have an increased risk of impaired neuropsychological development,” with delays reported in cognitive, emotional, and motor development, the researchers wrote.

The reasons for the link are not fully understood.

To find out if brain images showed changes that would explain neuropsychological impairment, a team of researchers in Denmark systematically searched databases for published studies reporting brain scan findings in children younger than 18 with neonatal cholestasis and a brain scan at time of diagnosis or later in life.

The search yielded more than 12,000 studies, but only 89 were eligible for review. In the 28 studies reporting data from 122 children with cholestatic disease or bile duct obstruction, biliary atresia was the most common diagnosis, found in 107 of the participants.

The majority of children underwent brain imaging scans within the first six months of life. Bleeding, or hemorrhage, was present in 54 of them.

“Hemorrhage in cholestatic children could be because of secondary vitamin K deficiency due to both fat malabsorption and inadequate dietary intake,” the researchers wrote. Vitamin K is a fat-soluble vitamin, the absorption of which is enhanced by bile in the intestines.

The second most common finding was signs of deposits of the essential mineral manganese, which may cause neurological problems, in the globus pallidus of 21 children from ages 0 to 11.

The globus pallidus is a brain structure involved in the control of voluntary movement. It also communicates with other structures that support functions like cognition.

This is the first study to systematically evaluate the association between neonatal cholestasis and findings on brain imaging.

Hemorrhage causes lasting cognitive impairment

“Hemorrhage is known to cause lasting cognitive impairment evaluated up to 5 years after diagnosis, suggesting that hemorrhage and previous hemorrhage play a role in neuropsychological impairment after neonatal cholestasis,” the researchers wrote. “Additionally, manganese deposition in [the] globus pallidus could also play a part.”

Five children had brain imaging scans before and after liver transplantation, which was conducted at a mean age of 6. After liver transplantation, abnormal findings disappeared in three of them and nearly disappeared in one. One child showed a reduction in an aneurysm, a bulging blood vessel, due to a rare cerebrovascular condition called moyamoya disease.

A study of 20 children showed that those with stable liver disease who had not had liver transplants had the most altered brain chemistry, followed by those who had undergone transplants, relative to a control group of children with acute liver failure.

Seven studies described children with neonatal cholestasis caused by infection. Two of these children showed cholestasis-related brain changes, including bleeding due to low levels of vitamin K, and altered brain chemistry during adolescence.

“This is the first study to systematically evaluate the association between neonatal cholestasis and findings on brain imaging,” the researchers wrote.

Researchers’ understanding of when disease-causing changes occur and how brain images change over time “would benefit from longitudinal studies through childhood to make it possible to make a correct and timely intervention to reduce future neuropsychological problems,” they wrote.

Changes in brain imaging may precede clinical manifestations of the neuropsychological impairment often experienced by children with neonatal cholestasis, but “clinical research with structured assessment is needed to map the prevalence and follow the changes over time,” the team wrote.