Hepatitis overview: What you should know

Last updated Feb. 1, 2024, by Marisa Wexler, MS

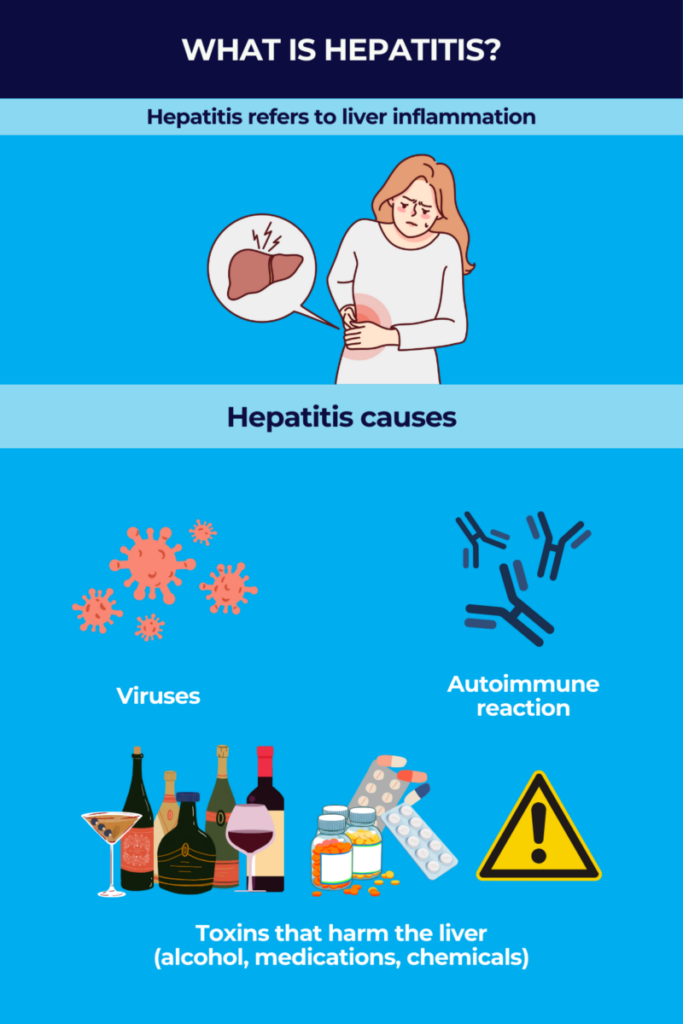

Hepatitis is a broad term that refers to liver inflammation. There are several types of hepatitis with different underlying causes — the most common forms occur due to a viral infection, while other types are due to an autoimmune reaction or toxins that damage the liver.

Hepatitis may be either acute — where inflammation lasts less than six months — or chronic, meaning inflammation that persists long term.

The severity of hepatitis can vary widely depending upon the specific type of disease and other factors. In some cases, hepatitis doesn’t cause noteworthy health issues, but in other instances it can lead to cirrhosis (extensive scarring of liver tissue that affects liver function), liver failure, or liver cancer.

Hepatitis types and causes

Hepatitis can be divided into different disease types based on the underlying cause of liver inflammation. Broadly, these types can be classified as viral or nonviral hepatitis.

Viral hepatitis occurs as a result of infectious diseases, where a virus infects cells in the liver. The immune system then launches an inflammatory attack to fight off the infection, ultimately leading to liver inflammation.

Five different viruses that can cause hepatitis have been identified to date; they are referred to as hepatitis types A through E (named in the order in which they were discovered). A sixth virus, dubbed hepatitis G, has been shown to infect the liver but hasn’t been proven to actually cause liver disease.

Nonviral hepatitis occurs due to reasons other than infection, including an autoimmune reaction where the immune system mistakenly attacks healthy cells in the liver. Nonviral hepatitis also can occur due to toxins or drugs that cause damage to the liver.

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is caused by the hepatitis A virus, which is typically spread via the fecal-oral route, meaning the virus usually infects people who have consumed food or water that is contaminated with fecal matter from someone infected. The disease also can be spread by person-to-person contact, particularly if small amounts of fecal matter are shared (e.g., from incomplete washing of the hands after using the bathroom). Because of the way it’s spread, hepatitis A is most common in areas with poor sanitation.

Symptoms of hepatitis A typically develop about two to six weeks after a person is first infected with the virus. The time between the initial infection and the appearance of symptoms is referred to as an incubation period. Although infected individuals don’t experience symptoms during the incubation period, they still may spread the virus during this time.

Unlike most other forms of viral hepatitis that frequently cause long-term liver injury, hepatitis A is almost always acute — about 85% of patients recover within three months, and almost all recover within six months. Hepatitis A infections are usually mild, but in some cases the acute infection can cause life-threatening liver failure.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there have been nearly 45,000 cases of hepatitis A documented in the U.S. since 2017. Hospitalization was needed in slightly more than 60% of these cases, but fewer than 1% were fatal.

Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B virus is spread via contact with bodily fluids. It’s most commonly spread from pregnant women to their babies, through sexual transmission, or through the sharing of needles or other contaminated medical equipment.

Hepatitis B typically starts off as an acute infection. Most of the time, the body eliminates the virus following the acute infection and no further disease occurs, but some people will develop chronic hepatitis B. The disease is contagious during both acute and chronic stages of infection.

The risk of developing chronic hepatitis B depends largely on the age of infection — as a rule, people who are younger at the time of infection are most likely to develop chronic hepatitis B. Only about 5% of people infected with the virus at age 6 or older develop chronic illness, while 30% of children infected younger than age 6, and up to 90% of babies infected during infancy, will develop chronic hepatitis B. Chronic hepatitis B can, over time, lead to life-threatening problems that include liver failure and liver cancer.

Hepatitis B is the most common liver infection in the world. It’s estimated that more than 2 billion people — about one-third of the global population — have been infected at some point, and more than 250 million people worldwide live with chronic hepatitis B. The disease accounts for most fatal cases of liver disease, and it is estimated to cause nearly one-third of cirrhosis-related deaths in the world.

Hepatitis C

Like hepatitis B, hepatitis C is spread via contact with infected blood or other bodily fluids. It’s most commonly spread by people sharing needles to inject drugs or via contaminated medical equipment; it also may be spread via sexual contact or from pregnant women to babies at birth.

After the virus enters the body, there’s an incubation period that can last anywhere from two weeks to six months, after which the acute stage of infection begins. For most people, acute hepatitis C infection doesn’t cause noteworthy symptoms — only about 20% of patients develop symptoms at this stage.

The acute phase usually lasts less than three months. Some people will clear the virus at this point, but most (about 80%) develop a chronic infection, with constant liver inflammation that continues to cause damage. About 1 in 4 people with chronic hepatitis C will develop cirrhosis within 20 years of becoming infected.

It’s estimated that about 60 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis C.

Hepatitis D

Hepatitis D, also sometimes called delta hepatitis, can only infect people who are already infected with the hepatitis B virus. Worldwide, about 5% of people with hepatitis B are also infected with hepatitis D.

Like hepatitis B, hepatitis D is spread via blood-borne transmission and contact with bodily fluids, which may include sharing needles or other contaminated equipment, as well as sexual contact.

Coinfection of hepatitis B and D (when people are infected with both viruses simultaneously) typically causes acute hepatitis with relatively mild symptoms, though it can be severe in some cases. Coinfection rarely leads to chronic disease — less than 5% of patients develop a chronic infection of these two viruses.

In contrast, superinfection of hepatitis D (when someone already infected with hepatitis B also is infected with the hepatitis D virus) commonly causes severe disease in the acute stage. Up to 90% of superinfected patients will develop chronic hepatitis D, in addition to the preexisting hepatitis B.

About 15% of patients with chronic hepatitis B and D infections will develop cirrhosis and/or liver failure within one to two years, and the majority (70% to 80%) usually experience these issues within a decade.

Hepatitis E

Hepatitis E, also sometimes referred to as enteric hepatitis, is in many ways similar to hepatitis A. Both are mainly transmitted via the fecal-oral route, meaning most people acquire the infection via food-borne transmission or drinking contaminated water, and both almost exclusively cause acute disease.

Symptoms of hepatitis E typically develop after an incubation period that can last anywhere from a few weeks to a few months. In the vast majority of cases, acute hepatitis E infection either doesn’t cause noteworthy symptoms, or the symptoms are relatively mild and go away in time.

According to the CDC, about 20 million people worldwide are infected with hepatitis E each year, but fewer than 1 in 4 of these infections cause notable symptoms. The mortality rate associated with hepatitis E infection is about 3.3%.

The risk of serious disease related to hepatitis E is higher in people who are pregnant, malnourished, or have other preexisting liver conditions. Hepatitis E also can be passed from a pregnant woman to a developing fetus, and it can cause serious pregnancy complications, including miscarriage and death.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is a rare form of liver inflammation that develops when the body’s immune system mistakes healthy parts of the liver for a threat and launches an attack that damages liver tissue.

As with most autoimmune diseases, it’s not clear exactly what causes autoimmune hepatitis to develop, although this condition is more common in people who have other autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, or inflammatory bowel diseases.

Autoimmune hepatitis can cause chronic disease, although treatments can substantially improve outcomes. Nonetheless, even with treatment, cirrhosis develops in about 15% of patients after a decade or two.

Toxic hepatitis

Toxic hepatitis occurs when the liver is damaged by toxins, chemicals, or drugs. Toxic hepatitis can be acute, in which case symptoms usually appear suddenly and shortly after exposure to the toxin, or it can be chronic, with symptoms not appearing for weeks or months after exposure.

Substances that can cause toxic hepatitis include:

- alcohol (sometimes called alcohol-induced hepatitis)

- over-the-counter pain medications, including acetaminophen (sold as Tylenol, among others), aspirin, ibuprofen (the active agent in Advil and Motrin IB), and naproxen (sold as Aleve and others)

- certain prescription medications, including some antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications, anticonvulsants, certain antiviral medicines, anabolic steroids, and statins (a class of drugs used to lower cholesterol)

- certain herbal supplements, including but not limited to aloe vera, black cohosh, and cascara

- certain industrial chemicals, including carbon tetrachloride, vinyl chloride, paraquat, and polychlorinated biphenyls.

Hepatitis symptoms

All forms of hepatitis can cause a range of symptoms — some cases might not cause any noticeable symptoms, whereas in others, the disease can cause serious and even life-threatening complications.

Common symptoms of hepatitis include:

- pain, swelling, or tenderness in the abdomen

- yellowing skin and eyes (jaundice)

- nausea and vomiting

- fever

- fatigue and malaise

- loss of appetite (anorexia)

- dark-colored urine

- pale or clay-colored stools

- joint and muscle pain.

Serious complications of hepatitis can include:

- cirrhosis

- liver failure (meaning the liver cannot work as needed to keep the body healthy)

- liver cancer

- high blood pressure in the liver (portal hypertension).

Hepatitis diagnosis

A hepatitis diagnosis involves looking for signs of inflammation and damage in the liver, as well as tests to identify the root cause. Common tests used to help diagnose hepatitis include:

- physical examination to look for symptoms and signs of hepatitis, as well as a detailed patient history to identify potential risk factors, such as heavy alcohol use

- blood tests, which may be used to look for markers of liver damage as well as signs of viral infection or an autoimmune attack

- imaging of the liver, such as a liver ultrasound or transient elastography, to look for structural damage and scarring indicative of liver inflammation

- liver biopsy, where a small piece of the liver is surgically removed and taken to a laboratory for analysis.

Hepatitis treatment

Treatment for hepatitis varies depending on the root cause of liver inflammation, the severity of the disease, and the individual’s health condition. Hepatitis treatment generally consists of supportive measures, such as ensuring a patient stays rested and hydrated, therapies for managing hepatitis symptoms, and in some cases, other treatments or medications to address the underlying cause.

In all forms of hepatitis, if the disease progresses to cause severe disease and liver failure, a liver transplant may be warranted.

Hepatitis A

There are vaccines that can help to prevent hepatitis A, but once the infection has occurred, there are no specific treatments for this type of hepatitis. Instead, management of hepatitis A focuses on addressing symptoms from the infection. Patients are generally advised to get significant rest, stay hydrated, and avoid alcohol and other substances that may stress the liver.

Hepatitis B

Prophylactic (preventive) treatments for hepatitis B include vaccines and hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG), a therapy that contains antibodies against the virus. Acute hepatitis B often doesn’t require specific therapy, but supportive treatments, such as fluids for hydration or therapies for pain relief, may be given if needed.

For chronic infections, especially if there’s active liver disease, medications may be used, including interferon therapies that boost the immune system’s ability to fight the virus, and antiviral medications.

Hepatitis C

There are no vaccines to prevent hepatitis C; however, a range of antiviral medications can be used to treat the infection. With modern antiviral therapies, both acute and chronic hepatitis C infections can be cured in more than 95% of cases after a few months of treatment.

Hepatitis D

Interferon therapies are currently the only treatment proven effective for hepatitis D, but even with these treatments, most patients will continue to have recurrence of the virus. There is no vaccine available for hepatitis D, but because the virus can only infect people also infected with the hepatitis B virus, vaccines to prevent hepatitis B also can help in preventing hepatitis D infection.

Hepatitis E

Similar to hepatitis A, there is no specific treatment for hepatitis E — most patients don’t require treatment. When treatment is needed, it focuses mainly on supportive care, such as making sure patients stay rested and hydrated.

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is mainly treated with medications that work to suppress the immune system, such as corticosteroids and/or azathioprine. These treatments can sometimes drive the disease into remission, although it’s common for autoimmune hepatitis to relapse and require additional rounds of treatment over the course of a person’s lifetime.

Toxic hepatitis

The main method for treating toxic hepatitis is to stop exposure to the chemical or drug that is causing damage to the liver. Supportive care, such as fluids for hydration, may be given, and in some cases other medications are used to help the body clear the toxin.

Prevention and risk reduction

For some forms of viral hepatitis, including hepatitis A and B, vaccines are available that can substantially reduce the risk of contracting the infection, and can help in the prevention of hepatitis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that all babies be vaccinated against hepatitis B as soon as possible, with the first vaccine dose being given within 24 hours after birth.

The WHO also recommends vaccination for hepatitis A as part of routine vaccination schedules for children ages 1 year and older in parts of the world where this infection is common. Hepatitis A vaccination also is recommended for people at increased risk of encountering the virus, such as those traveling to places with a high prevalence of the disease.

In addition to vaccines, taking steps to minimize the risk of infection can help to prevent disease. For hepatitis A and E, which are mainly spread by contact with trace amounts of feces from people infected, robust sanitary practices can help to limit spread.

For hepatitis B, C, and D that are spread by contact with bodily fluids, preventive steps can include using barrier methods of protection during sex (such as condoms), using properly sterilized medical equipment, and not sharing needles or other items (razors, toothbrushes, etc.) that can come in contact with a person’s blood.

Preventing toxic hepatitis mainly involves limiting exposure to potentially harmful chemicals and drugs, such as limiting alcohol use, using medications only as directed, and using appropriate safety gear when working with dangerous chemicals.

Living with hepatitis

Hepatitis can cause unique challenges, and patients with chronic forms of hepatitis may require lifelong medical care to monitor and manage the disease.

Hepatitis also can bring emotional and social difficulties — depression and anxiety, for example, are commonly experienced by people with the disease.

Navigating life with a potentially serious illness can be daunting, but many resources, including support groups and patient advocacy organizations, are available to help people with hepatitis live life to the fullest.

Some of the groups that offer support for hepatitis patients include:

- American Liver Foundation

- Autoimmune Hepatitis Association

- Chronic Liver Disease Foundation

- Coalition for Global Hepatitis Elimination

- National Hepatitis Corrections Network

- Help‑4‑Hep

- Hepatitis B Foundation

- Hepatitis C Association

- Hepatitis C Caring Ambassadors Program

- Hepatitis Foundation International

- National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable

- World Hepatitis Alliance.

Liver Disease News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

Recent Posts

- Distinguishing between PFIC3, Wilson’s disease key for optimal outcomes

- The different ways fatty liver disease affects women vs. men

- Who would’ve guessed a child growth chart would be my nemesis

- New blood test helps spot hidden liver scarring earlier

- Livmarli clears severe skin growths in 2 boys with Alagille syndrome