Our son’s Alagille diagnosis was our introduction to rare diseases

Joining that community meant learning a new language

Before having our son Finley, our exposure to the rare disease world was limited. Most people we’ve encountered since receiving his diagnosis have had the same experience. Unless you personally know someone with a rare condition, knowledge about these diseases can be hard to come by.

When our doctors told us about Alagille syndrome, we had no idea what it was. From that moment on, we started learning what I’ve come to call our “second language.”

I’ve shared here how we’ve drafted our “Alagille elevator pitch.” It was prompted by the many times we told people about our son’s diagnosis and their response was, “Oh, I’ve never heard of that.”

I think I can count on one hand the number of people I’ve met who’ve heard of Alagille syndrome, unless they have a family member with the condition. When we say “be rare with Finn,” we mean it. Alagille syndrome affects approximately 1 in 30,000 to 45,000 people.

Learning the language of Alagille

Learning a language is hard. It can feel even more frustrating when the language is your own, but you aren’t versed in the science. My wife, Dani, and I weren’t among those who loved science in school. A special shoutout to Dani, who dove headfirst into learning this new language.

Through all of the doctor visits, more new terms would come our way. Dani became a master pretty quickly. She’s the type who needs to know all the details. I, on the other hand, have struggled to learn them. It’s been a challenge for me — not because of the content, but because I’ve had a harder time facing the realities that come with a rare disease diagnosis for your small, beautiful child.

In this way, Dani and I balance each other out. She knows everything, sometimes too much. I may not know every single detail about Alagille syndrome, but between the two of us I tend to bring more optimism when we face a new obstacle. Sometimes this trait is a great thing; sometimes it can be incendiary. Those are the moments when we’re like oil and water.

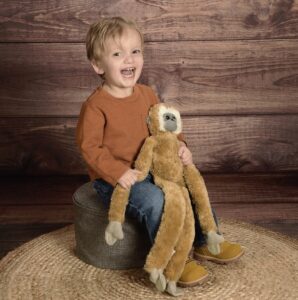

Now that Finley is nearly 3.5 years old, we’ve found ways to work through our different methods of managing our shared experience with a rare disease.

The frustrating part for me about learning this new language is that no matter how much we know, those around us will never fully be able to understand it as we do. I don’t expect them to. We have some incredibly supportive family and friends who’ve learned a whole heck of a lot about Finley’s Alagille diagnosis over the past three-plus years. But they can never be expected to speak the language the way we do as parents.

Finding people who speak our language

Through a few channels, Dani and I have found ways to plug into the Alagille community. One of my favorite things about meeting more people affected by Alagille syndrome is finding conversation partners who speak your second language.

I’ll never forget the first time we had that experience of speaking to another parent of a child with Alagille syndrome. They understood us. They could ask the right questions. We could ask them questions instead of feeling like we could only provide explanations. It was a truly cathartic experience.

We’ve since had the opportunity to provide that same experience for a few other families. It’s a special feeling to be able to pass that catharsis on to someone else. There’s a lot of pain and anxiety that comes from living in the rare disease world, but with those challenging emotions can come positive, healing ones. Something as simple as finally speaking to someone who gets it can help you feel that others understand your situation.

I don’t think I ever understood the full extent of the impact that advocacy work can have. I hope to continue writing this column as a way to demonstrate that, yes, you may feel alone navigating your own rare disease journey, but if you look in the right places, there are others who speak your language. Find those voices, and the journey is less daunting than it once seemed.

Note: Liver Disease News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Liver Disease News or its parent company, Bionews, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to liver disease.

Comments