Targeting mitochondrial problems eases cholestasis in mouse model

Cell powerhouses identified as potential therapeutic target for disease

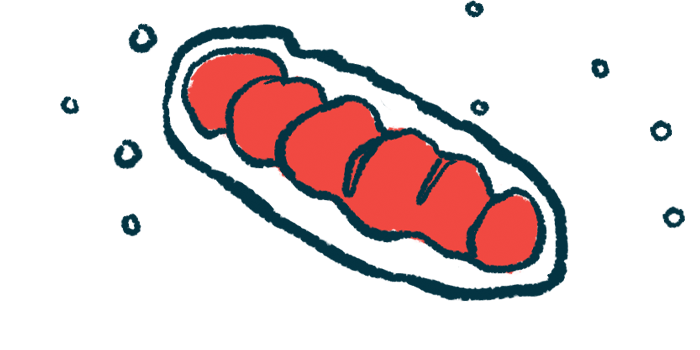

Problems in mitochondria, the cell’s powerhouses, may contribute to liver damage associated with cholestasis and represent a potential therapeutic target, a study showed.

Deteriorating mitochondrial function was found to be associated with old, tired hepatocytes, the main liver cell type, which accumulated with cholestatic liver injury. In this state, called senescence, cells age, display signs of damage, and they no longer divide, but do not die.

When researchers specifically alleviated mitochondrial dysfunction in hepatocytes of a mouse model of cholestasis, they found a reduced number of senescent hepatocytes and less cholestatic liver injury.

“These findings confirm the deteriorated effect of hepatocyte senescence in cholestatic liver injury and highlight that targeting mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated hepatocyte senescence may aid the treatment of cholestatic liver injury,” researchers wrote.

The study, “Mitochondrial Dysfunction-mediated Hepatocyte Senescence is Involved in Cholestatic Liver Injury,” was published in the journal Free Radical Biology and Medicine.

Experiments conducted in patients, mouse models, lab-grown cells

In cholestasis, the flow of the digestive fluid bile from the liver to the intestines stalls or slows. When it backs up in the liver, bile can damage hepatocytes and cause scarring, or fibrosis, leading to cholestasis symptoms.

“In patients with chronic liver diseases, hepatocytes have many senescence-associated characteristic changes,” the researchers wrote, adding that an increase in senescent cells has been reported in some of these diseases.

While mitochondrial dysfunction has been shown to contribute to hepatocyte death in people with cholestatic liver diseases, “the involvement of mitochondrial dysfunction-associated senescence in cholestatic liver diseases remains unclear,” the researchers wrote.

To clarify this potential involvement, a team of researchers in China conducted a series of experiments in people with cholestasis, mouse models of the disease, and lab-grown mouse hepatocytes.

First, they demonstrated an increase in senescent cells with increasing cholestasis severity. Liver samples from cholestasis patients with cirrhosis, or irreversible liver fibrosis, had significantly more hepatocytes testing positive for P21, a molecular marker of senescence, than samples from people with milder fibrosis.

Similarly, the team saw significantly more P21-positive hepatocytes in a mouse model of cholestasis than in healthy animals.

In this mouse model, the team tested the effects of DpC, a compound that can kill senescent hepatocytes. DpC treatment significantly reduced the number of P21-positive cells, infiltration of inflammatory cells, and fibrosis markers, suggesting “senescent hepatocytes contribute to the progression of cholestatic liver injury,” the team wrote.

Improving mitochondrial problems may have therapeutic effects

Next, the researchers collected and analyzed hepatocytes from healthy and cholestatic mice. They found that several mitochondrial function-related pathways, including those involving the sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) protein, were significantly reduced in hepatocytes from the injured mice.

SIRT3, a protein that helps promote mitochondrial activity and address cellular stress, was found to be particularly involved in mitochondrial dysfunction and hepatocyte senescence in cholestatic disease.

Exposing lab-grown healthy mouse hepatocytes to a compound that induces senescence resulted in significantly lower SIRT3 levels and in signs that mitochondria weren’t working properly.

Genetically modifying these cells to produce less SIRT3 exacerbated mitochondrial changes and increased the number of P21-positive cells. In contrast, modifying the cells to produce more SIRT3 partially alleviated signs of mitochondria dysfunction and senescence.

[These findings highlight that] “mitochondrial dysfunction-induced hepatocyte senescence partially contributes to the decline of liver function, [liver] inflammation, and fibrotic changes in cholestatic liver injury.

In cholestatic mice, a treatment designed to increase SIRT3 production specifically in hepatocytes resulted in significantly fewer P21-positive cells, indicating less senescence, as well as reduced liver injury and fibrosis.

Together, “these results reveal that senescent hepatocytes are characterized by mitochondrial dysfunction in cholestatic liver injury,” and that “SIRT3 downregulation-induced mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in hepatocyte senescence in cholestatic liver injury. the researchers wrote.

These findings highlight that “mitochondrial dysfunction-induced hepatocyte senescence partially contributes to the decline of liver function, [liver] inflammation, and fibrotic changes in cholestatic liver injury.”

The data therefore suggest that efforts to improve mitochondrial function and reduce senescence in hepatocytes may have therapeutic effects in cholestatic liver disease. Future research could test this hypothesis and develop experimental therapies based around this idea.